the interiority of deep summer.

my new desert noir short story, what i've been reading, and various summer goings-ons.

A few writing updates:

My desert noir meets sci-fi short story, “The Ice House at the Edge of the World,” was published on The Fabulist – you can read it here. It’s the first short story I’ve published since my collection, Assemblage, came out last year!

A review of Foundations by Hayli May Cox went up on Heavy Feather review. Among other things, she said: “Perhaps what I most love about this book is its portrayal of women’s love for each other and, even when it’s difficult, their love for themselves.” – read the whole thing here.

I was also interviewed by Caelyn Cobb for Your Impossible Voice, which I never shared here, but very much enjoyed participating in – read it here.

---

I turned 37 last weekend – which feels impossible, but I’ve accepted it. We went dancing and to the art museum and the movies and ate ramen in Japantown and drank dry martinis with olives, it was a perfect weekend.

The weather has been gorgeous in California, and we’ve spent the beginning of summer camping, swimming, and lazing in the sun like great humanoid lizards. What this really means is I’ve spent my time reading in different places, while the sun creates crisscross lines on my body, depending on which bikini I’m wearing that day.

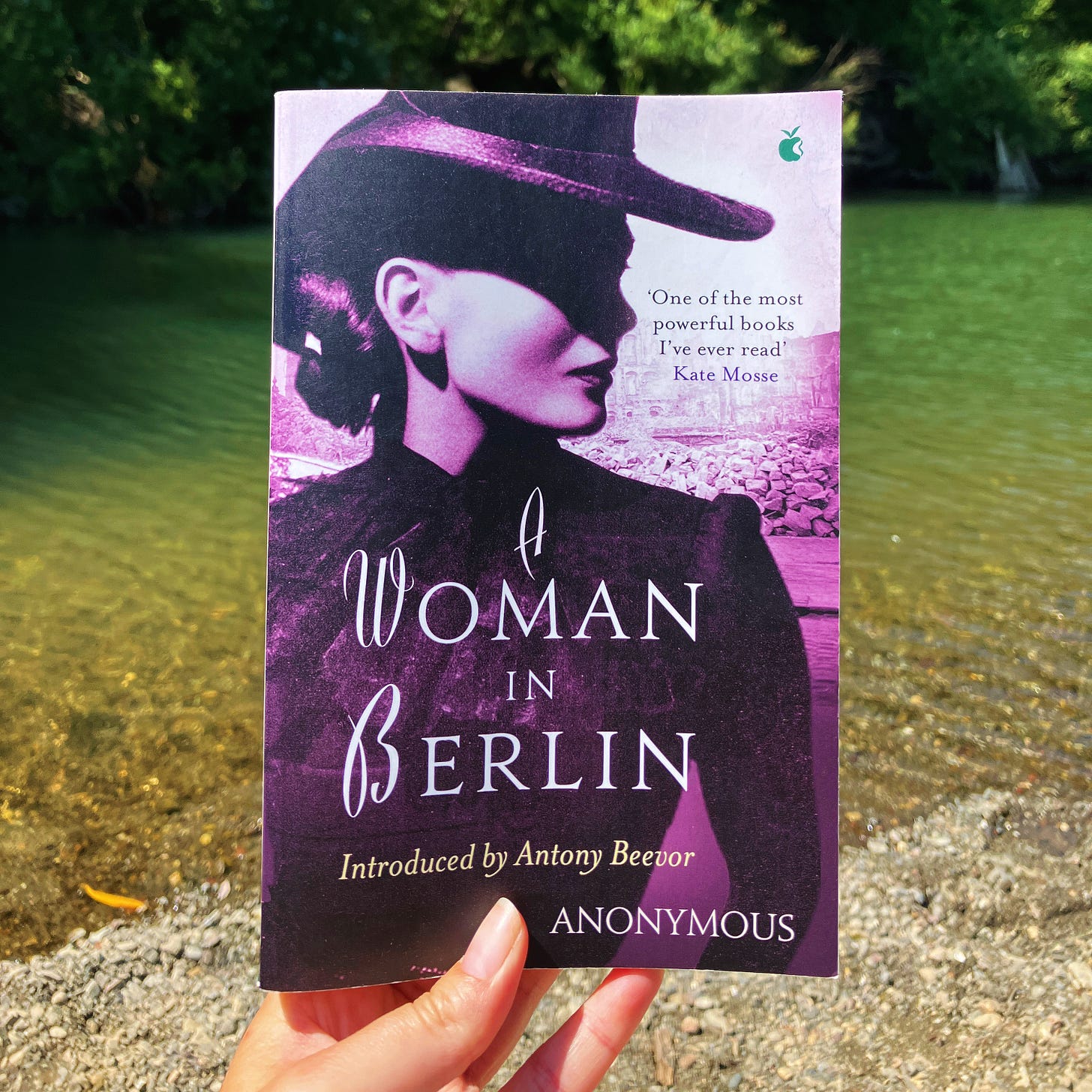

I read A Woman in Berlin with my toes in the Russian River, and I would not hesitate to say that this first-hand account of the Russian occupation of Berlin, told from an anonymous 34-year-old female journalist’s perspective, is one of the most important historical accounts of WWII I’ve ever read. She confronts the horrors of war with gallows humor and an unflinching eye.

Although the book only spans an 8-week period it’s over 300 pages in length. It is readily apparent to the reader that writing in this diaristic format is one of the only coping mechanisms the journalist has to process her ordeal. She begins writing Russian phrases on the back pages to appear as though she is studying the language of her captors.

The people in the apartment block where she lives create odd little family units and the narrator finds herself living with a widow and her male tenant after her own top floor apartment is bombed. Despite their previous camaraderie formed underground in the bunkers, most of them turn their backs on one another after the Russians arrive – there’s not enough food, not enough space, they don’t want women who ‘tempt’ the Russian soldiers living under their roof. It was difficult not to compare it with the recent pandemic and how quickly any sort of community turns to only self.

She spins out the days in minute detail: women living under the constant threat, and often the actuality, of rape, the lack of food and water, the inability to clean oneself, the fear of STDs, the bombed-out buildings that smell of feces. All the while asking, what am I living for? And, what must I do to ensure my survival?

When it was published, the book was not well received in Germany. The German people wanted to forget the war and what their women suffered, despite the fact that A Woman in Berlin is written without political agenda or any sort of intentional spin. She is unsparing is providing an account of the cruel details inherent in war, particularly those inflicted on women, which are most often the ones overlooked. The book gained an underground feminist following and was only recently republished, after the author’s death, to a new audience with the ability to view her work with fresh eyes.

I read Mild Vertigo by Mieko Kanai while I laid on my deck in a sports bra drinking sparkling wine from a can – the effervescence carried from the narrative to my mouth. Originally published in 1997, this novel explores the daily life of Natsumi, a housewife living in a Tokyo apartment with her husband and two young sons. Natsumi only keeps in touch with a few friends from her school days, otherwise her conversations take place mostly with other women in the apartment complex. For the most part, her life seems entirely predictable, yet Natsumi is content.

Kanai describes the interior landscape of the housewife, her knowledge of where to go in the supermarket, the predictability of her household routines, the never spoken wish that she’d had daughters instead of sons. Natsumi’s thoughts loop and digress in a way that made me think of Ducks, Newburyport, and there is something dizzying about the listing of her mundanity. In a trance-like state, Natsumi observes the water coming out of her tap and watches it become dazzling, interlacing ropes. She tries to explain this physical sensation of coming out of herself during one of her rote tasks to her husband, who makes no effort to understand.

I guess you don’t do the dishes very often, but what if you’re brushing your teeth, say, do you not ever just find yourself staring at the water as it rushes down the drain? And it’s strangely pleasant, that feeling, of course it’s no big deal, but you kind of zone out, as if you’re dreaming, although it’s not any dream in particular that you’re having. And then you come back to yourself with a jolt as you realize that you’re wasting water, I guess you just wouldn’t understand it as a man, especially one who so rarely does any form of housework, Natsumi said to her husband, and her husband raised his eyebrows in a way that suggested both slight irritation and a modicum of concern, making a face that meant, what are you trying to say, exactly?

Coupled with Kanai’s critical analysis of a photo exhibit she slyly inserts into the narrative, we see this admiration of the everyday juxtaposed with the heady rush of an imagined career woman, as most of Natsumi’s female friends are. These critical essays are written in an entirely different style than Natsumi’s narrative, but ultimately come to parallel her life – the seemingly banal photos provide a backdrop for the viewer that they feel comfortable watching with detachment, as they might observe the life of a housewife.

Both A Woman in Berlin and Mild Vertigo deal with a claustrophobia of both physical place and within one’s own mind. These women are imprisoned, by wholly different circumstances, in apartment blocks where they only interact with the people within their unit. The worlds they know are interior ones, rich with detail and escapism, and the outer world falls away with the ongoing need for survival, in whatever form.