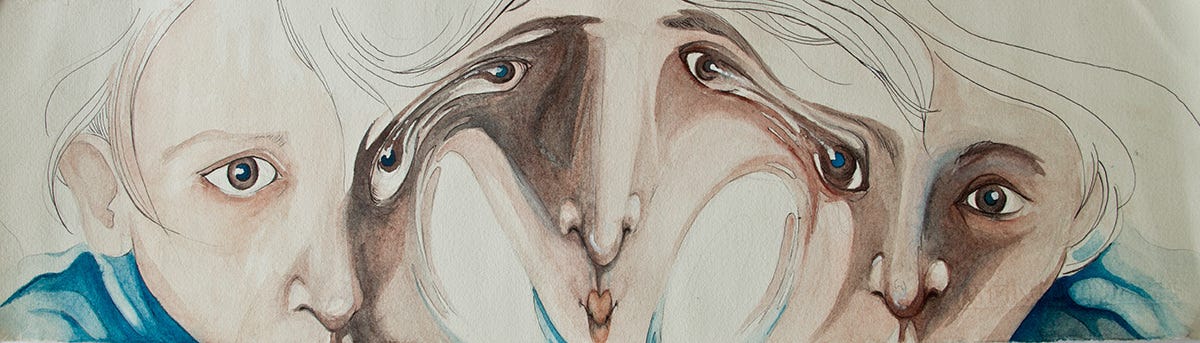

distortion.

thoughts on authenticity, creativity under a digital gaze, and what I've been reading lately.

I was watching a Twitch streamer discussing a recent conflict in the gaming community and he said: “We used to go to these tournaments for fun… just for fun, if you can believe that.” Now, the thought is that many players have sponsors and what they say is monitored and branded, they themselves are human commodities pandering to an often overly invested audience.

That same day, I read a post on Instagram from a music artist who stated:

“… we’ve allowed market forces and ‘the algorithm’ to whittle our creativity down to the lowest common denominator. Everything has to be the most generic, the most conventional, the most universally palatable it could possibly be, otherwise no one will ever hear / see it.”

Have we given up our collective creative voice to make what is palatable rather than what is real? When someone hits upon their ‘thing’ in the algorithm, when they go viral, do they stop pushing themselves or experimenting? Would we rather be monetized brands or humans experiencing joy?

Most artists explore similar themes across a variety of work. The distillation and reexamination of similar topics simply means you haven’t said all you needed to say about it yet. I feel closest to my authentic self when I am writing, as I imagine many artists do, so I delve into the topics and queries I feel most passionately about. However, the definition of ‘authentic’ is often altered by the many masks we are forced to wear (I’ve seen this phenomenon best exemplified by the viral meme where people shared the different personalities they have for Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn) I’ve watched artists I admire move from the experimental to mimetic reproductions of the ‘thing’ that got them noticed and I am left wondering again about their lived artistic experience.

Coincidentally, or perhaps not, I’ve been reading A Horse at Night: On Writing by Amina Cain and she touches upon some of the same questions.

“In the last year I’ve become fixated on the idea of authenticity. This is partly because I feel at times I have lost sight of my authentic self, and I want more than anything to come close to it again, or at least to feelclose to it. For me, authenticity means that how I act and what I say and how I actually feel around others is aligned, that I am connected to myself and to another person at the same time. I want my writing to be authentic too, for every sentence to reach toward honesty and meaning.”

Similar to Kate Zambreno’s Drifts, A Horse at Night explores the act of writing through the keeping of a diary and allusion to inspirational works of fiction — which left me with an exhaustive recommendation list by the end of it. Cain explores her own writing process in relation to the complex nature of art, interior landscapes, and the contemporary experience of fiction.

As a fan of Cain’s previous work, I found this slender book both engrossing and meditative. I’m sure I will return to it.

She ends her musings on authenticity with:

“My loss of authenticity is related to change, to how, as I’ve gotten older, I seem to have become a different person. … I am more rigid and there has been a loss too of the freedom I once felt, when the world felt entirely open, and utterly beautiful.”

Which made me think of another book I recently read and enjoyed lately, Is Mother Dead by Vigdis Hjorth (translated by Charlotte Barslund). In it, the narrator is estranged from her family because she chose to make art that authentically represents the way she understands the world, thus upsetting her parents whose rigid view of propriety and family dignity clash with her own in a way the narrator finds hypocritical.

“The lie some people need to live can be the undoing of others.”

Many writers I know have said something along the lines of, ‘I can not write the memoir until [blank] has died,’ for fear of disappointing a family member or friend. The story Hjorth writes is one that asks, ‘what if you did though?’

In Is Mother Dead, Hjorth returns to her exploratory probing of complex family units. The narrator fictionalizes her estranged, elderly mother, the mother of her youth, she empathizes with her and creates a present mother which only exists in her own imagination — the reality is something else entirely. The repetition in the narrator’s mind creates a layered suspense, blurring the lines between what is truly in the past and what is present.

I love Hjorth’s writing, the fragmentary collections of moments that create suspenseful narratives are a style all her own. Her settings are often snowbound, and I save her books for the winter, when I can read them under an electric blanket.

Over the next week, I hope to have time to compose a year end wrap up of sorts and send that out to y’all before the year’s end. In the meantime, stay warm and remember: it can probably wait until next year.

Been thinking about a lot of the same stuff lately. Can't wait to read A Horse at Night!